Placing Hands on the God: Diving Deeper into “Doing Things” Series: #1

© Matthew Whealton 2020

Background and Purpose of the Series

This post is the first in a series that will look more deeply at the elements of the rituals used by The Temple of Ra in San Francisco and other Temples in the Kemetic Temple Collective, all founded by or under the guidance of Richard Reidy. These rituals are published in Richard Reidy’s two books Eternal Egypt: Ancient Rituals for the Modern World (Reidy 2010, 204-297) and Everlasting Egypt: Kemetic Rituals for the Gods (Reidy 2018, xxxiv-xxxviii), which form the core of the Kemetic Temple Collective (KTC) ritual practices. Both contain their own explanations of the rituals and are recommended for further clarification and for the many rituals they cover – all adapted from major texts from the Egyptian ritual corpus.

First, I should explain part of the title – that is, the words “Doing Things” in double quotes. “Doing Things” is the literal translation of one of the ways Ancient Egyptian describes what we today call rituals – especially those used in Temples. The compound word itself is ı͗r.t-ı͗ḫ.wt . Although it is a quasi-technical term in this meaning, a more loosely bound phrase made from the same words can be used in a number of contexts, often non-religious ones. These usually have positive connotations – to act or gain things productively, rightly, successfully, and the like.

The series will initially work through the ‘Brief Daily Ritual’ first published in Eternal Egypt, then updated in Everlasting Egypt. This simple, brief ritual is intended as a practical shortened version of the longer rituals we perform that can be done daily as a part of personal practice. I’ll focus on the updated version in Everlasting Egypt, since that corresponds best to our practices these days. Before proceeding, be aware that these forms are a suggested set of ritual actions and accompanying words – each person can add more to the framework or do less of it according to personal capabilities, time constraints, and preference. What is important is forming a daily practice, not setting up a difficult, elaborate, or expensive ritual that gets in the way of the practice itself.

Each post will examine the ritual action and the utterance that goes along with it, their history and places found (briefly), and take a deeper look at what is being said and why particular Gods, Goddesses, places, and themes are invoked or otherwise mentioned in them. I hope this last part will be useful to other practitioners and Kemetics. These are my own insights and findings from both research and practice and I need to say they represent no ‘official’ dogma or teaching of the KTC Temple Family, much less any kind of commentary or critique of other Kemetic groups’ ritual practices.

Placing Hands on the God: Diving Deeper into “Doing Things” Series: #1

Since I have already written several times in Imperishable Stars about the very first action in the Brief Ritual, the ‘Awake in Peace’ salutations, (see Pantheacon 2016 Presentations under Waking up Gods, Waking up Creation: The Egyptian Morning Hymn and Waking Karnak and A New ‘Awake in Peace’ Hymn for Nut), I’ll start our series with the second action, called ‘Placing Hands on the God/Goddess’ (rdı͗.t ꜥ.wy ḥr nṯr/nṯr.t).

Documents and Monuments with this Ritual Action

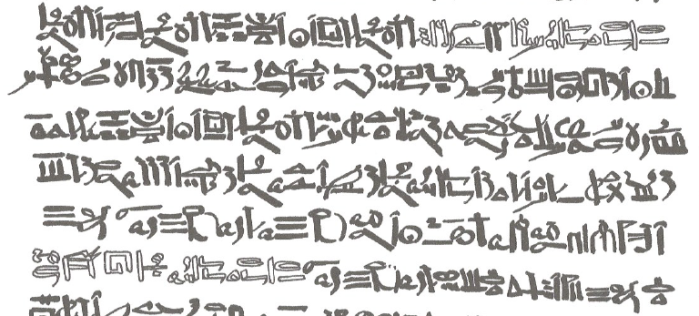

All texts use hieroglyphic script except pAmun and pMut, which are written in hieratic. All are in Classical Middle Egyptian (‘Égyptien de tradition’) with some Late Egyptian spellings and rare Late Egyptian grammatical patterns.

All of these versions are very closely parallel, with the Exception of the Utterance in the Wabet at Edfu Temple. (Since that version is not used in Richard Reidy’s Brief Daily Ritual, I will not discuss it further):

Dyn 18 – Luxor Temple: Rooms XVIII, XIX (Scene or Title + Scene) (Braun 2013, 68-71)

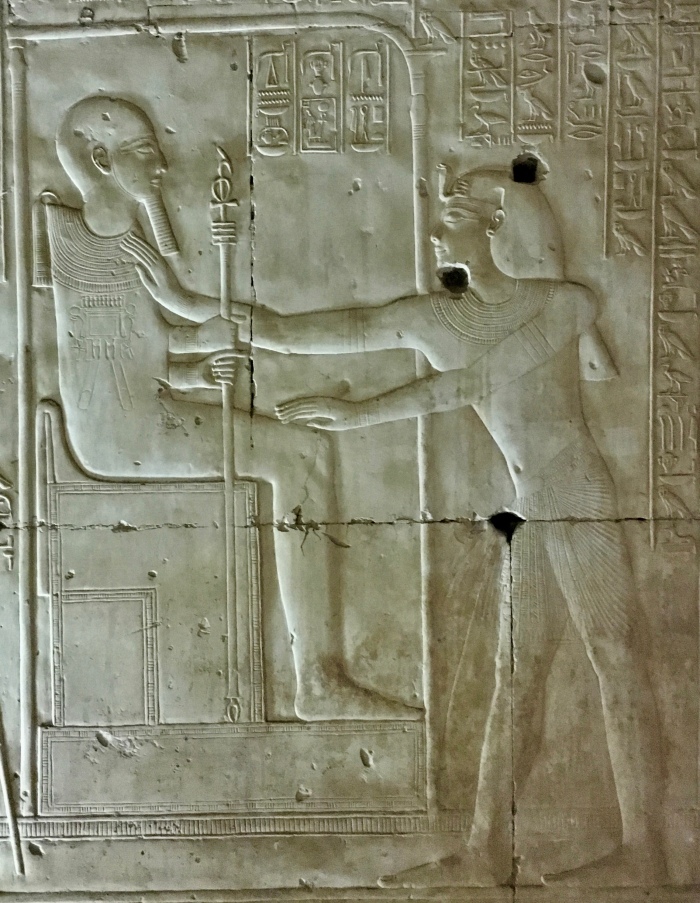

Dyn 19 – Temple of Millions of Years of Seti I Abydos: Scene 7 in Chapels of Ptah, Re-Horakhty, Amun-Re, Isis, and Horus (Title + Scene + Utterance) (Calverley and Broome 1933, Calverley and Broome 1935, Braun 2013, 72-74; 158-159, David 2016, 140-141) (see Note 1)

Dyn 19 – Temple of Millions of Years of Seti I Gurna: Sanctuary of Amun-Re (Braun 2013, 75-76)

Dyn 22 – PAmun Berlin P. 3055: Utterance 44 (Title + Utterance) (Anonymous 1901, 26: Plate XXVI, Moret 1902, 167-170, Braun 2013, 76-78; 158-159)

Dyn 22 – PMut Berlin P. 3014 and P. 3053: (Utterance 44) (Title + Utterance) (Anonymous 1901, 54-55: Plate XXI-XXII, Moret 1902, 167-170, Braun 2013, 79; 158-159)

Ptolemaic – Edfu Temple: Wabet: North Wall (Title + Scene + Unique Utterance – not treated here)(Cauville, Devauchelle et al. 1987, T. I, Fasc. 3: 420.9-421.3, Hussy 2007, 22-23, Chassinat 2009, T. IX: Plate 33a)

The ritual action and utterance titled “Placing (his) Two Hands Upon the God” forms a part of the large set of Actions known as the Daily Temple Statue Ritual. (Other actions and other ritual sequences will be described as we need in the coming posts). Richard Reidy used as his primary reference the book Le Rituel du Culte Divin Journalier en Égypte by Pierre Moret, published in 1902 (Moret 1902). Since then, more of the ritual texts have been found and published and the translations have been improved. As you might imagine the scholarly literature on the topic has grown massively. In preparing this series, I will be using a number of scholarly references. In this post particularly, I am using several much more recent sources, especially Nadja Braun’sPharao und Priester–Sakrale Affirmation von Herrschaft durch Kultvollzug: Das Tägliche Kultbildritual im Neuen Reich und der Dritten Zwischenzeit (Braun 2013) . Braun’s book offers new translations of both the ritual papyri and the texts in the Seti I Abydos temple, as well as pointers to other important secondary literature. I have also relied on insights from additional publications (see Note 2) and my own experience in performing these rituals in various forms on a near-daily basis. Performing the rituals has led to questions as well, some of which I hope to address here in a way that is both experiential and ‘scholarly’ as much as possible. Again, this adds up to the important takeaway that these are my own thoughts. They are not meant to be a set of single answers that block other insights or other questions. I’d truly appreciate readers here commenting on their own thoughts and readings, and so create a real discussion. I will ask only that you place your comments in the framework of understanding the polytheistic reality of Ancient Egyptian religious ritual practice. The focus here will be on the rituals attested and documented from the native Egyptian records.

The Text from Everlasting Egypt and its Meaning

Here is the text of “Placing (his) Two Hands upon the God” as Richard Reidy excerpted and adapted it. It is short and simple:

Djehuty has come to you. Awake when you hear his words.

I have come as the envoy of Atum.

My two arms are upon you like those of Heru.

My two hands are upon you like those of Djehuty.

My fingers are upon you like those of Anpu (Anubis).

Homage be to you. I am a living servant of (name of Deity).

As you can see the text is short and rather simple, at least on the surface. So, let’s look at it more closely and ask a few questions. What is placing arms on the God all about? Why are these four particular gods involved and named? Why is the priest doing the ritual acting as these gods and acting on their behalf? What does this segment of the ritual actually ‘do’?

Let’s take these questions one at a time. (Well, sort of. They do interact as well).

The first question asks ‘Why is this action titled Placing (his) Two Hands on the God’? This action relates to the ritual sequence itself, to creation, and to the mythic cycles of the Sun God Ra and Osiris. In answering this question, we’ll focus on creation. We will return to the other aspects in answering subsequent questions. One of the stages of creation in the Heliopolitan Solar Cosmogony is the first creation of separate gendered beings (Shu and Tefnut) by the Creator God Atum. After the actual creation act, Atum brings them to life by embracing them to bestow on them their Kas (their Life Force). Some texts mention that breath was also involved. Atum’s act can be called the “Ka embrace”. This ritual action recapitulates Atum’s original embrace and the ongoing creation of new beings and brings us to a very important concept in Egyptian ritual practice. Each day, the Gods and their Temples are awakened from sleep at about dawn, when the rising sun is itself seen as the moment of creation, repeating itself each day. The statues of the gods undergo (re-) creation as well in the temples by means of the performance of the Daily Rituals.

The second question is about the four named Gods involved. The first is Atum, whom we have already met as the Creator who grants life force in the Ka Embrace. For the next three Gods, the mythic frame and imagery shift to the complex of events that make up the Osiris/Horus/Set cycle, with a bit of other cycles brought into focus as well. I will not retell these various accounts here, though. For a good introductory account, you can consult Geraldine Pinch’s book “Egyptian Mythology” (Pinch 2004). Books by Eric Hornung and James Allen are helpful as well (Hornung 1982 (1996), Allen 1988, Hornung 1992).

After Atum, Horus is mentioned next. Horus plays many roles in Egyptian thought. Here, he embodies two different roles: 1) his role as the one who wakes his father Osiris and assists when his father rises on one side during the revitalization of his reassembled body; and 2) his role as healer – known as Horus, Physician of the Gratified/Content God (the Sun God Re) (Gardiner 1935, I: 55-57; II: Plates 33-33a, Leitz 2003, VI: 215.3-216.1) (see Note 3). Note that the arms of Horus are the instruments here, emblematic of his lifting his father up on his side.

Then we come to Djehuty, who places his hands on the god in the ritual. Djehuty is also a kind of healer, the one who finds and restores to health the Wedjat Eye of Horus, literally “the Sound/Undamaged (Eye)”. He returns what had been lost and damaged in a whole and completely functioning form, using his hands to give back the Eye.

Finally, Anubis places his fingers on the god. Anubis is the one who presides over making the body into an eternal, perfect, and ‘noble’ form in the process of mummification, so it may reside in its ‘House of Gold’ (the coffin and/or the burial chamber in a tomb or the Shrine of the God or Goddess of the ritual). He is also the Protector of the dead and the sites of burial as he wanders the desert cemeteries by night. One way he does this is by placing the Seven Akhu spirits on and around the mummified body and sarcophagus (see Chapter 17, Section 21 of the Book of the Dead) (Quirke 2013). These acts of tying and placing imply a precision appropriate for the fingers.

Our third question asks why the priest acts as these four gods and on their behalf. We’ve covered some of the background in the previous two questions. There are two overarching reasons: The first is to recreate the original creation moment (the “First Occasion” – zp tpy or sp tpy in Egyptian). The second is to recapitulate the return of Osiris to life and the healing and restoration of his body that must precede that return to life. Both of these relate to the reawakening deity in his/her image each day in the early morning.

Now, before going further into why that is necessary in the ritual, let’s look a bit deeper into the translation of the text and also into some extra context from the original papyri. All the translations have similar wording when it comes to the lines phrased like ‘My two arms are upon you like those of Horus’. Here it is good to notice that the actual Egyptian phrase is closer to ‘My two arms are upon you as Horus’ or ‘My two arms are upon you in Horus’ or even ‘My two arms are upon you with Horus’. This is not to quarrel with the existing translations, since they read more naturally in English (or German or French) the way they are. But my point is to show that the relationship between the arms of the priest and Horus is much more direct than ‘… like those of …’ implies. They are identifications with the god’s arms, not similes or metaphors for them. The Egyptian version uses a single preposition here, whose core meaning refers its object to a location, often ‘in’. The preposition relates that the arms are located in, with, and as (i.e. ‘in the capacity of’) the god named that is its object (Allen 2014, 106).

Another important aspect of this utterance is that the papyrus originals are longer than the excerpted adaptation that is part of the short ritual from Eternal Egypt and Everlasting Egypt. In the papyri, Osiris and Sokar are greeted before the excerpted text portion, which locates the ritual action in the context of the Osiris and funerary mythic complexes, just as the statement equating the officiating priest as envoy (see Note 4) of Atum locates the action in the context of the creation complex. The placing of the hands therefore not only reperforms the act of creation on the image of the god or goddess, it also resurrects the image from a state of death. That state of death is itself part of the day and night cycle and ties to the nightly journey of the Sun through the underworld where he and Osiris briefly join and renew each other. The image also undergoes this joining during the placing of hands ritual action. The location of the joining of Ra and Osiris is the Mound of Sokar in the underworld, which provides the reason why Sokar is also invoked in the complete ritual text. One other element in the longer text brings into play the ‘day of presenting sand’. There are at least two conceptual bindings that guide the mention of sand. The first is tied to Sokar, upon whose mound of sand the joining of Ra and Osiris occurs in the Underworld. The second relates to placing the image onto a layer or mound of sand in order to undress, purify, and re-clothe it during the ritual actions following action #44 – Placing Two Hands on the God. In the full Temple Statue Ritual, action #44 follows after the Awake in Peace, some initial offerings and purifications, and the opening of the shrine to reveal the god’s image. After those actions, the priest performs action #44 before then lifting the image out of the shrine to place it on the sand in preparation for the later actions. A similar mound of sand forms the platform for placing a statue or mummified body in the Opening of the Mouth ritual (Otto 1960 I: 1-2; II 34-36).

The fourth question asks what this ritual action actually does. Well, it both brings the image to life again each day as part of the ongoing cycles of creation and rebirth and restores it and makes it ‘perfect’. This is just one of the 60 or so ritual actions of the Daily Temple Statue Ritual. There are many more that also act to reanimate, recreate, restore, nourish, protect, and rejuvenate it. The majority of all the actions also serve to bring the god into a state of soundness and well-being and peaceful gratification.

It is important to realize that these long and complex rituals have no one specific ‘magic’ moment or climax, as a person might expect from a sequence built on the kind of narrative or expository arc that is a structuring principle of Western and modern literature. They instead build up a strongly self-reinforcing structure of multiple mythic cycles, with multiple gods and goddesses participating along with the priest to recapitulate creation and its components, each itterance bringing different sets of concepts and components into play. We saw this in the placing of hands action in miniature. And that is the key to what this ritual act does, with all the others: By restoring and recapitulating creation and its cycles of day/night and life/death, it restores Maat and upholds Maat. This actualized goal is accomplished by the joint efforts of humans performing the rituals and acting ethically alongside the Gods and Goddesses themselves. Therefore, ritual is a joint responsibility and duty of humans and gods to maintain this creation and keep the forces of chaos and destruction at bay. Much more can be said about the implications of this core Egyptian concept and the mechanisms used to accomplish it, but that is a discussion for another time.

As one last observation on the text, the statement ‘Homage be to you’ as found in Richard Reidy’s books, is nowadays usually translated as ‘Greetings’, ‘Greetings to you’ or ‘Hail to you’. This is more accurate. The phrase literally means ‘May I inquire about (greet) your face’ or ‘May your face be greeted’ (Allen 2017, 244). It is a very polite way to greet the god or goddess, not a pledge of fealty or subservience in the European sense of ‘homage’.

Tips for Contemporary Ritual Practice: An Exercise

As we near the end of this first installment of the Diving Deeper series, let’s return to the practicalities of performing this rather simple ritual action. Here is a brief exercise to increase your awareness and ‘mindfulness’ when performing the Placing of (his) Two Hands upon the God ritual action on the basis of the discussion in this post. There are some physical gestures and some mental recitations involved – like this:

(Begin with hands in the Dua ‘Praise’ position)

Djehuty has come to you. Awake when you hear his words.

(As you say these words, take a step forward toward the image)

I have come as the envoy of Atum.

(Briefly raise your arms slightly and turn the palms inward to make the ‘Ka’ sign)

(Then place your right hand on the left shoulder and you left hand on the right wrist of the image. Keep your hands in place for the rest of the action and utterance.)

(Take a breath and exhale it as you visualize Atum, the Creating Sun of Heliopolis)

(Mentally recite ‘Atum, who grants to you your Life Force’)

My two arms are upon you like those of Heru.

(Take a breath and exhale it as you visualize Horus, the all-seeing falcon and successor to his father Osiris)

(Mentally recite ‘Horus, the Physician, who wakes and heals you’)

My two hands are upon you like those of Djehuty.

(Take a breath and exhale it as you visualize Djehuty, the Divine Mediator and Magician)

(Mentally recite ‘Djehuty, who returns the Eye, and makes you whole again’)

My fingers are upon you like those of Anpu (Anubis).

(Take a breath and exhale it as you visualize Anpu, the Jackal headed Lord of the Divine Booth)

(Mentally recite ‘Anpu, who makes your body perfect and who protects you’)

Greetings to you. I am a living servant of (name of Deity).

(Remove your hands and either briefly return them to Dua position or place them at your sides)

You may use this as a way to familiarize yourself with the content of the action, and make the embodiment of the Gods more complete as you perform the ritual. Once your visualization is strong, you won’t need to recite the extra words mentally. I do find that taking the time for a breath and exhalation helps to give time to let the words of the utterance work, though. Try it and let me know your experiences.

Final Thoughts

I hope that this rather long post will assist you in understanding the richness and meaning of the Placing Two Hands on the God and help deepen your own practice. Future episodes in the series may not need to be so long, since we have covered a lot of the preliminaries and some basic background here. The thoughts and comments I’ve presented are by no means exhaustive. I have abridged and selected the possibilities, since the amount of ancient and scholarly literature connected with this topic are immense. You can read the appropriate sections in Richard Reidy’s two books for more information, along with the other books and articles in the bibliography below. Also, feel free to write a comment on your own thoughts and questions on this ritual action and on subsequent posts. If we know anything about the Egyptian way of thinking about these matters, it is that there are always multiple ways of conceiving them.

Next Time: Utterance for the Second Libation

Stay tuned!

Notes

Note 1:

I use Moret’s and Braun’s numbering system. David 2016 refers to this action as ‘Episode 13’.

Note 2:

Among others, see (Shafer 1997, Quack 1999, Dunand and Zivie-Coche 2004, von Lieven 2012)

Note 3:

I am reading this epithet (swnw nṯr ḥtp) differently from Gardiner and Leitz Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen, based on the position of ḥtp and the usual intransitive sense of this verb. For a transitive reading (‘The Physician soothing the god’ (Gardiner) or ‘Der Arzt, der den Gott beruhigt’ (LGG) ) we would expect sḥtp instead of ḥtp. Another possible reading given the word order would be ‘The Gratified/Content Physician of the God’ (taking ḥtp as an adjective modifying the direct genitive phrase swnw nṯr ‘The Physician of the God’). A further consideration is that Gardiner comments that the meaning is uncertain, citing a passage in The Dialog of a Man and his Ba. Allen’s recent treatment of this text provides an entirely different reading of the passage involved (Allen 2011, 40).

Note 4:

The text papyrus witnesses write wpw.t ‘task, mission; message’, not wpw.tı͗ ‘messenger, envoy’ (Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae Lemmas 45750 and 45760, respectively http://aaew.bbaw.de/tla/ ): ı͗ı͗.n=ı͗ m wpw.t n ı͗t < =ı͗ > Itm. Thus, the literal translation is properly ‘I have come on a mission of <my> father Atum’ or ‘I have come with a task of <my> father Atum’. Since this makes very little difference to the sense of the utterance, there is no real reason to amend the translation as found in Moret’s and Reidy’s books. Note as well that Richard Reidy’s adaptation excerpts the word(s) ‘<my> father’. This segment of the text is differently worded in the Abydos shrines.

Bibliography

Allen, J. P. (1988). Genesis in Egypt.

Allen, J. P. (2011). The debate between a man and his soul: a masterpiece of ancient Egyptian literature. Leiden, Brill.

Allen, J. P. (2014). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs 3rd Edition, Cambridge University Press.

Allen, J. P. (2017). A Grammar of the Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts: Volume 1: Unis. Winona Lake, Indiana, Eisenbrauns.

Anonymous (1901). Hieratische Papyrus aus den Königlichen Museen zu Berlin, I: Rituale für den Kultus des Amon und für den Kultus der Mut. Leipzig, J. C. Hinrichs.

Braun, N. S. (2013). Pharao und Priester–Sakrale Affirmation von Herrschaft durch Kultvollzug: Das Tägliche Kultbildritual im Neuen Reich und der Dritten Zwischenzeit. Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag.

Calverley, A. M. and M. F. Broome (1933). The temple of king Sethos I at Abydos, volume I: the chapels of Osiris, Isis and Horus. London; Chicago, Egypt Exploration Society; University of Chicago Press.

Calverley, A. M. and M. F. Broome (1935). The temple of king Sethos I at Abydos, volume II: the chapels of Amen-Rē’, Rē’-Ḥarakhti, Ptaḥ, and King Sethos. London; Chicago, Egypt Exploration Society; University of Chicago Press.

Cauville, S., et al. (1987). Le temple d’Edfou I, 3. Le Caire, Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

Chassinat, É. (2009). Le temple d’Edfou IX. Le Caire, Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

David, R. (2016). Temple ritual at Abydos. London, The Egypt Exploration Society.

Dunand, F. and C. Zivie-Coche (2004). Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE. Ithaca, NY; London, Cornell University Press.

Gardiner, A. H. (1935). Hieratic papyri in the British Museum: third series: Chester Beatty gift.

Hornung, E. (1982 (1996)). Conceptions of god in ancient Egypt: the one and the many. London; Ithaca NY, Routledge & Kegan Paul; Cornell University Press.

Hornung, E. (1992). Idea Into Image Essays on Ancient Egyptian Thought. New York, NY, Timken Publishers.

Hussy, H. (2007). Die Epiphanie und Erneuerung der Macht Gottes: Szenen des täglichen Kultbildrituals in den ägyptischen Tempeln der griechisch-römischen Epoche. Dettelbach, Röll.

Leitz, C. (2003). Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen, Peeters Publishers.

Moret, A. (1902). Le rituel du culte divin journalier en Égypte: d’après les papyrus de Berlin et les textes du temple de Séti Ier, à Abydos. Paris, Ernest Leroux.

Otto, E. (1960). Das ägyptische Mundöffnungsritual. Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz.

Pinch, G. (2004). Egyptian mythology: a guide to the gods, goddesses, and traditions of ancient Egypt. New York; Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Quack, J. F. (1999). “Magie und Totenbuch – eine Fallstudie (pEbers 2,1-6).” Chronique d’Égypte 74(147): 5-17.

Quirke, S. (2013). Going out in daylight – prt m hrw: the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead; translation, sources, meaning. London, Golden House.

Reidy, R. J. (2010). Eternal Egypt: Ancient Rituals for the Modern World, iUniverse.

Reidy, R. J. (2018). Everlasting Egypt: Kemetic Rituals for the Gods, iUniverse.

Shafer, B. E., Ed. (1997). Temples of ancient Egypt. Ithaca NY; London, Cornell University Press; I.B. Tauris.

von Lieven, A. (2012). “Book of the Dead, book of the living: BD spells as temple texts.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 98: 249-267.

Excellent elucidation of this important ritual! Thanks very much!

I am reminded–I just thought I’d mention in passing!–of the common and now cliche mistranslation of the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, and the idea of “As Above, So Below,” which in the earliest versions of that text now available to us–in Arabic (translated from Greek or Coptic, most likely), as well as the earlier pre-Corpus Hermeticum Latin translations–don’t really say that in a metaphorical/similie fashion, but instead in a more direct way…essentially, it isn’t that what is “Below” is similar to that which is “Above,” but instead it is that “What is Above is made from/comes from that which is Below, and that which is Below is made from/comes from that which is Above.” This says a lot more about the human/divine co-creative role, and has implications for things like apotheosis, etc. (which is of course always an interest of mine!), and takes the whole idea not just from realizing that one is a kind of “cog” in the great divine unfolding, at least in ideal form, but instead that what one is doing here is created by what is happening in the divine worlds, and what is happening and existing there is also created by that which is done here. It’s a much more useful way to deal with ritual, and to emphasize the importance of ritual action, etc., than the more typical way this part of the text is understood! That, in what you explain in this post, one IS the various Deities doing the various roles in relation to the Divine Image concerned is quite similar: had They not done these things originally, we would not be able to do them, and as we do them, this makes a particular set of divine realities come into being…!

Brilliant! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind words on this post. Thanks also for the better interpretation of that famous adage from the Hermetica. Although the Hermetica and the Western Esoteric Tradition that sprang from it are not my focus, I think the ‘as above’ trope has been used in a very superficial way in recent times. The contemporary magical approach seems to not get the deeper responsibilities implied by the dialogic nature of its equation and unification of one duality out of so many possible ones. And it has unfortunately emphasized mechanized and mechanistic equivalencies in the interest of a kind of self-interested magical thinking. There is no ‘giving-back’ or ‘paying-forward’ in that superficial view, no responsible reciprocity, and no ‘human/divine co-creative role’ (as you write) in the much larger, ever-changing and ever-productive ‘apotheosizing’ cosmovision and cosmogenesis that I believe is essential to how we understand Egyptian thought-ways.

LikeLike

Precisely…and that is exactly how too many people deal with not only this passage, but also so much else involved in Mystery traditions. It’s seen as a tool for self-empowerment, and it comes at the expense of relationship-building, reciprocity, and co-responsibility. If one can just stop with “Well, I’m like The Above now, so my responsibility to others ends here!” and that’s that, it explains why so many efforts at building community amongst pagans and polytheists have so utterly failed, because if that is the (small “a”!) apotheosis of the path and the ultimate realization/culmination of it, then it is narcissistic, self-interested, and focused entirely toward the (myopic and solipsistic) inner and the (pejoratively characterized) “below” than it is on the (usefully and correctively) outer and the (superiorly characterized) “above.”

It’s amazing what amounts to a few conjunctions misplaced for verbs can entirely shift a mindset and create a culture that is quite contrary to what was originally intended! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic article! The rituals are worthy subjects for study. They become richer and more personally involving the deeper you go, and they provide a lifetime of learning. My research into Kemetic religion came to a grinding halt when my worklife took over everything, but this article makes me want to look back into it again. When people like you post your insights it provides a window for enrichment of the whole community, whether or not we follow the same path or even agree.

I look forward to further articles from you. This might even lend itself to a great series of discussions to hold within the temple.

LikeLike

The part about the “fingers of Anpu” reminds me of the two finger amulets, found in mummy wrappings usually near the embalmer’s incision. I know very little about this particular amulet, all that I know comes from one paragraph in Carol Andrew’s “Amulets of Ancient Egypt.” Here she supposes that the fingers might represent those of the embalmer, and may either reaffirm the embalmment process or provide additional protection to the incision through which the embalmer worked. Since Anpu was the first embalmer, and all embalmers of ancient Egypt identified with Him during their work, you might say that these are the “fingers of Anpu.” Also, they bear a resemblance to the protective gesture we make towards the four directions in ritual, and which was also a protective gesture warding off crocodiles. Because of this use of the two fingers as a protective gesture, I favor the later interpretation of the amulet as protection over the vital point at which the embalmer entered the deceased’s most personal space.

I see strong resemblances between the “fingers of Anpu” reference and the two fingers amulet. Because the two fingers amulet is only seen in Late Period per Carol Andrews, it is more likely that it was inspired by the ritual Utterance rather than the other way around. At any rate this is all speculation, but interesting to me. Perhaps the “fingers of Anpu” are a protective ward over the vital point where the priest enters the netjer’s most intimate space to perform this procedure of giving life?

LikeLike

Weben Banu, thank you for your thoughts and insights in these two replies. Your contribution on the Two Finger Amulet is spot on! More on that in a moment, but first I would like to encourage you to pick up those studies again. I believe we need many voices and points of view to enrich our ways of thinking and practicing as Kemetics. That said, it is important that we work hand in hand with the ancient texts and objects to keep ourselves from losing sight of their meaning and intent in Egyptian thought and practice (as far as it is possible for us to discover them). It takes educating ourselves to do that. And it also takes not being afraid of changing our minds as knowledge improves. We must also not be afraid of deviating from those ancient practices when they are no longer constructive for our contemporary lives. Of course, I know you know these things, but want to reiterate the point for folks who are new or outside of our circles.

I looked into the literature on the Two Finger Amulet and tracked down the original source of what Carol Andrews wrote. It is from a paper from 1935 by Alan Shorter, who was himself writing about funerary amulets from the British Museum, where Carol Andrews was a curator. The basic ideas which Shorter, Andrews, and you state seem to still be the consensus view. There is not much literature out there that I can find, but a paper by Michel Pezin and Francis Janot in 1995 adds some information. They analyze the Unclassified signs Aa2 and Aa3 ‘pustule’ as representing two fingers drawing closed an open incision. They further tie this to the incision in the left flank in mummification. The Amulet itself represents a magical indicator and guarantee of the embalmer’s/Anubis’s two fingers drawing the incision closed. They date the earliest use of the Two Finger Amulet to “around the 26th Dynasty”, where it complements earlier use of a plate of wax, copper, bronze, or gold over the incision site.

Here are the references:

Andrews, C. (1994). Amulets of ancient Egypt. London, The British Museum Press.

Pezin, M. and F. Janot (1995). “La “pustule” et les deux doigts.” Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 95: 361-365.

Shorter, A. W. (1935). “Notes on some funerary amulets.” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 21(2): 171-176.

LikeLiked by 1 person